Should I spend time learning pitch accent?

I discuss what is pitch accent, how to learn it, and whether it is worth you time.

This is a common question among Japanese learners. Pitch accent study has gained quite a lot of traction these years, mainly thanks to YouTubers like Dogen and Mattvsjapan. What are pitch accent’s benefits? Is it worth the time invested? Can you ever master it? Aren’t you better off just ditching it?

By the end of this article, you will:

- Have a basic understanding of Japanese pitch accent and how it is notated in dictionaries;

- Know what good it does to have or not have a correct pitch accent;

- Have an idea about the cost (time, effort) of learning pitch accent;

- Be able to decide for yourself whether you want to pursue pitch accent study and to what extent;

- Be introduced to a few different ways of improving your pitch accent and incorporating pitch accent study into your Japanese learning routine.

A bit of vocabulary

For you to read this article more comfortably, let me first define a few words:

- Mora: The phonological unit of Japanese. It’s like our syllables, but it also counts ん’s’s, っ’ss and long vowels as one unit. In this article, I will mainly speak about morae.

- Downstep: Also sometimes referred to as the ‘accent’ of a word. This is the place in the word where the intonation drops (more on that later).

- Numeric notation: A way of indicating where the downstep occurs in a word. Often used in dictionaries, it’s a number in a box like this: 3⃣. I write it as [3].

What is pitch accent?

What are its characteristics? How is it written?

English’s word stress vs Japanese’s pitch accent

In English, word stress makes us emphasise certain vowels, such as wonderful or incredible. This stressed syllable is characterised by three distinct features:

- It is louder;

- It is higher in pitch;

- Its vowel sound can never become a schwa.

Forget the third one; I’ve included it for the sake of completion, but this is beyond the scope of this article. If you’re curious about what a schwa is and want to know more, feel free to click on the link I provided above. What is important to retain here is that English has both a change in pitch and volume.

Japanese, as opposed to English, only shows a change in pitch. This is why we speak about pitch accent.

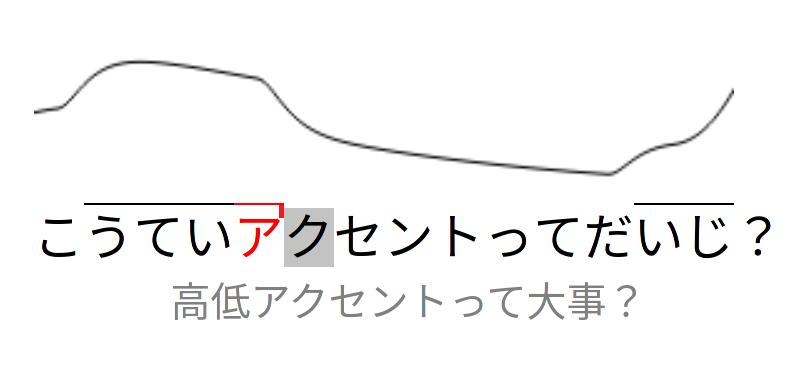

High and low pitches, and why it’s better to talk about downsteps

Since Japanese has changes in pitch, this means there are higher and lower pitches. One way of teaching Japanese pitch accent is to talk about high (H) and low (L) pitches. For example, the word ネコ would be HL while the word イヌ would be LH.

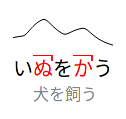

The problem with this approach is that it is binary: you only have two levels. Real Japanese, however, can have more than two levels. Take the sentence イヌヲカウ, イヌヲ would be LHL and カウ HL. However, the resulting sentence doesn’t sound like LHLHL unless it is read slowly and carefully. When speaking at an average speed, most people would say something like MHMML where M is a middle pitch.

This is why instead of writing long strings of H and’s, we can say that this sentence has two downsteps—one at the end of イヌ and one on the first syllable of カウ. The NHK Japanese Pronunciation Dictionary shows pitch accent in words as downsteps instead of high and low pitches. The sentence then becomes イヌ\ヲカ\ウ.

I heard about atamadaka, odaka, nakadaka, what are they?

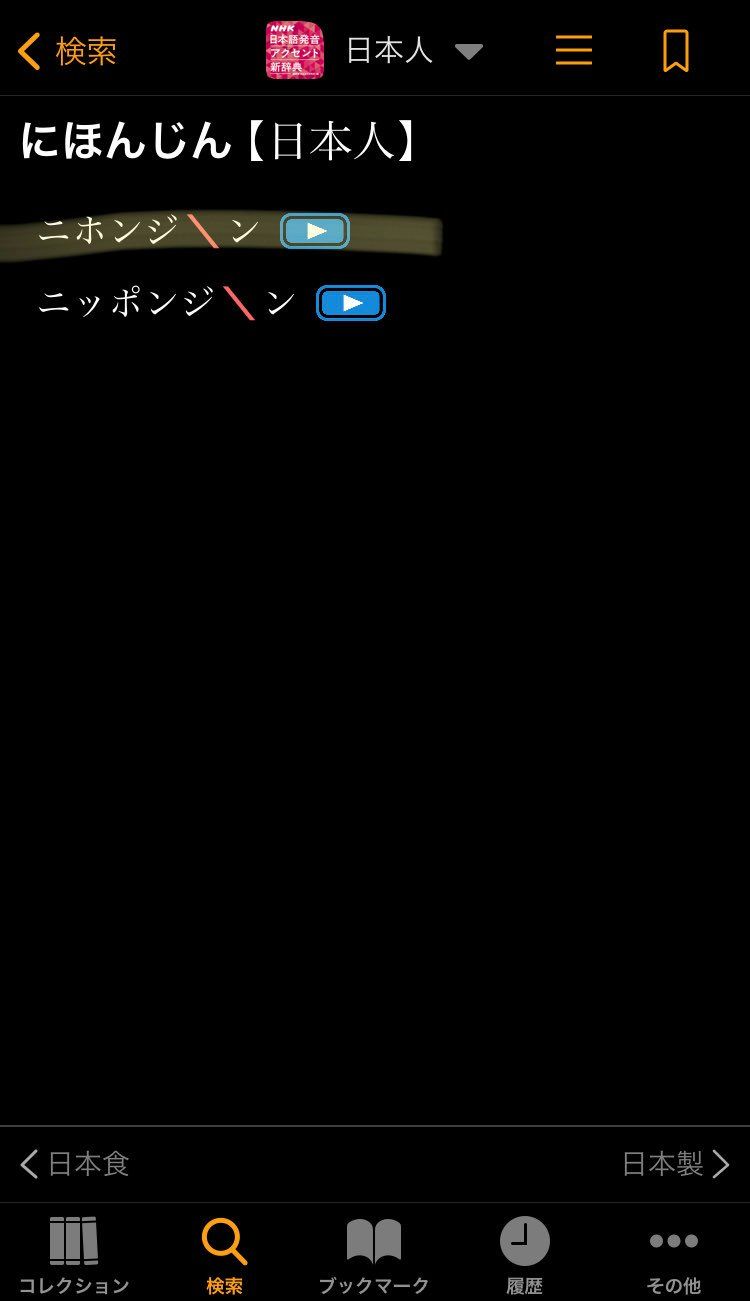

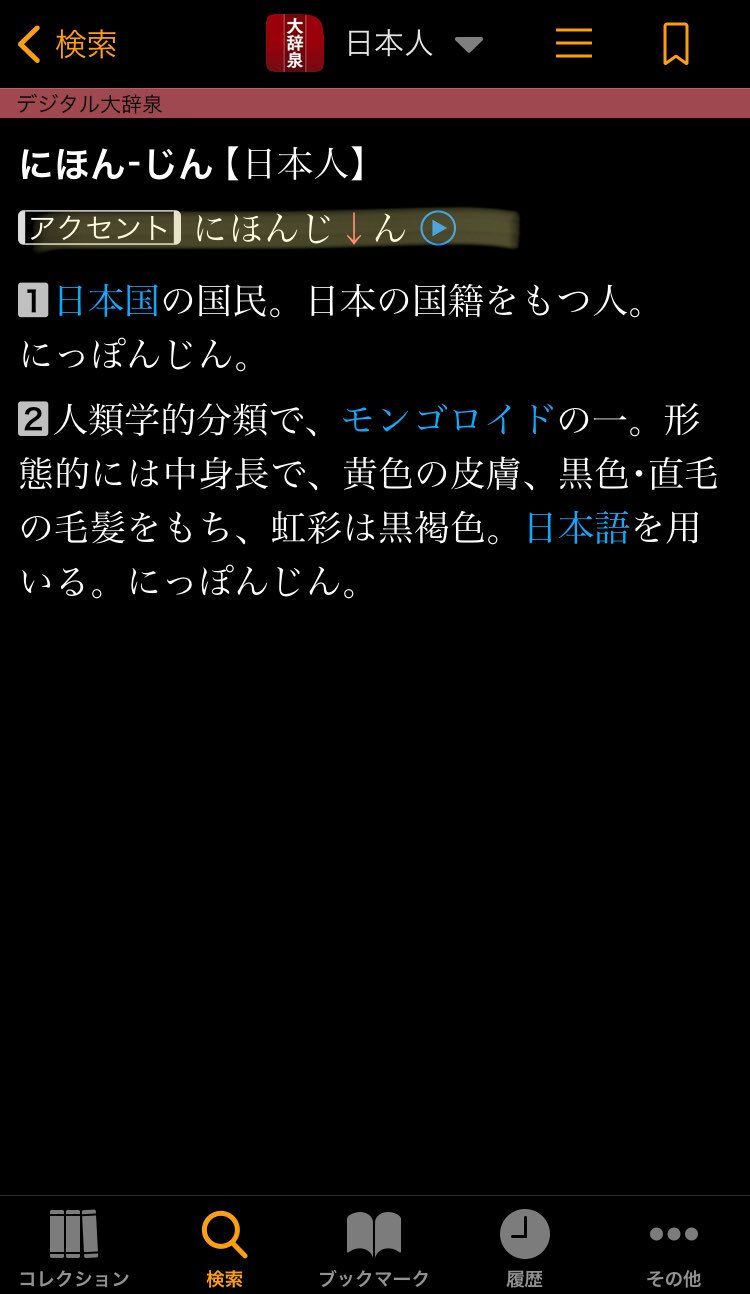

These are types of accent patterns. 頭高 is just a way to say that the downstep occurs on the first syllable of the word; 尾高 is on the last one; and 中高 manifests itself inside of the word. I don’t dislike these words, but I don’t find them particularly helpful either, especially nakadaka, which doesn’t give any information on where exactly in the word the downstep occurs. This is why dictionaries don’t use these but indicate where precisely the downstep is located with a symbol like in ニホンジ\ン or にほんじ↓ん or a number like in 日本人[4].

from left to right: NHK Accent Dictionary, Daijisen, Daijirin

How do the numbers work?

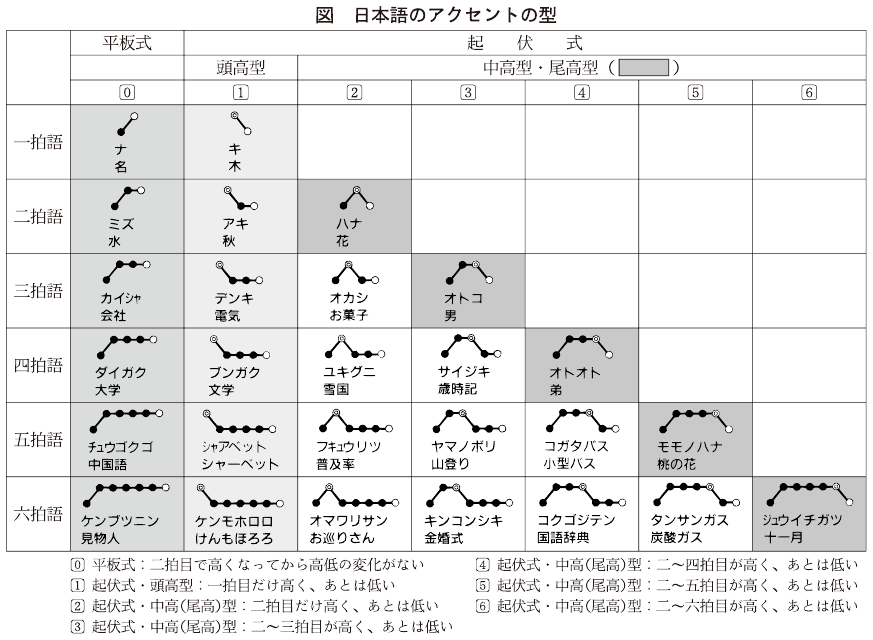

You might have come across this table, or maybe it’s the first time you see it. Nonetheless, it looks intimidating and complex. And it shouldn’t, because the principles behind it are very simple. Let me explain it to you.

Forget the table. To understand how to use the numeric notation, you only need to know these four things:

- The first and second morae of a word always have different pitches;

- If the downstep is not on the first mora (this means if it’s anything but [1]), the first is always low, and the second always rises;

- The mora after the downstep always drops in pitch;

- Once the pitch falls, it only goes back up gradually.

Back to the scary table. Look at the last row: no matter the length of the word, the pitch always starts low and rises on the second mora. The only exception is if the word is atamadaka; then it always starts high and drops immediately. This means that we don’t need to indicate when there is a rise because the rising pitch is a fixed rule of Japanese phonology and can be inferred by the reader. We only need to indicate where in the word the downstep occurs.

This is what the number indicates. It tells us after which mora the pitch falls. In the case of ア\キ it’s [1]. For ハナ\ it’s [2] because the pitch of the following particle falls. For ミズ where there is no downstep, it’s simply [0].

Was it easy to understand? Don’t hesitate to reread this part; I promise it will make sense!

Studying pitch accent

When? How? Why?

How long does it take to learn pitch accent?

How long is a piece of string? Yeah, about double that amount.

More seriously, the basic rules of pitch accent do not take too long to grasp and can make your Japanese sound more natural. Look at you; you’ve read this far and know quite a few things about pitch accent now! The tricky part is remembering the pitch accent of individual words, but this process takes an entire life, just like learning new vocabulary in any language.

When should I start studying pitch accent?

The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The second best time is now.

I like this saying. By the way, can we take a moment to think about how weird it is that we accept so many quotes as ‘Chinese proverbs’ thinking twice about it? I’ve looked online, and there is no such saying in Chinese.

Back to the subject: The best thing to do is to start as early as possible. This way, you can associate each new word with its correct pitch accent from the beginning. It’s all about forming good habits. You might think it’s too much to remember, but if you’re familiar with the numeric notation, which you should now be, it’s just one tiny additional bit of information to add to each word. It’s too different from remembering the grammatical gender of a word when learning German or Russian. This is far from impossible.

It’s even more straightforward for verbs and adjectives because there are only two sorts: those with a downstep and those without. If there’s a downstep, it’s always on the same mora. You only have to remember which of the two groups the word belongs to.

How can I study pitch accent?

There is no one definitive method, but here are a few of my recommendations:

Anki: It has been beneficial for incorporating pitch accent learning into my study routine. You don’t need to create your own cards: many Core shared decks offer cards with audio, where the pitch is indicated using numeric notation or graphs.

Speaking to oneself: I’ve been using this method for many years with great success. Repetition, repetition, repetition. This is the best way to drill a particular pitch and have it become second nature so you can speak without thinking about it. Of course, talking to someone is better, but you won’t always have a volunteer on hand, so monologuing in your car, in the shower, or wherever you can get away with it without people thinking you’re a lunatic is my go-to method.

Recording oneself: Output alone without feedback does not help much with improvement. When you speak, much of your attention is used to think about what you say and how you say it. When you hear yourself back, you’d be surprised at how many details you can hear that you didn’t even realise.

Listening back to yourself, especially several months later, is embarrassing for all of us, but these recordings, months and years later, are also an excellent way to hear how much progress you’ve made, which helps keep you motivated.

Shadowing is a viable approach, but you should know the pitch accent basics beforehand to do it with maximum efficiency.

Japanese Phonetics Course: created by the YouTuber Dogen. I have not used this resource and have only skimmed through his free content, but I’ve heard great things about them.

What I would recommend in terms of the order would be:

- The very general rules of pitch accent;

- Rules for compound words;

- Rules for verbs and adjectives;

- Individual accents for words and verbs themselves, which you learn as an integral part of learning new vocabulary.

Acquiring a good ear for pitch accent through practice will allow you to be more conscious about it when you hear spoken Japanese, which will help you pick up the pitch of new words more easily. It’s not automatic, though; you have to make a conscious effort to actively listen for pitch and try to reproduce it. Don’t count on being able to pick it up by passively consuming Japanese media.

What if I already have bad pitch accent habits?

Nothing is irreparable. It will, however, require more time and effort to undo your bad habits. Record yourself speaking/reading, compare that with a native recording and adjust. Don’t be shy about repeating the correct version many times so that it sticks, especially if you already have formed bad habits.

The brain is highly plastic. You only have to know how to use this to your advantage. Repetition will reinforce the synaptic connections for a particular action, and you’ll be able to perform that action more efficiently. You first need to consciously use pitch accent so that it can become an unconscious part of your speaking.

A word of advice: correcting a bad pitch requires time and good habits. If you can’t invest yourself, or you do not have a good reason motivating you to correct your pitch accent, I suggest you work on other things that you feel you’ll need more, depending on your goals. If you’re doing something but can’t see the meaning behind it, it’s tough to follow through.

Do I need to know pitch accent?

That’s it. The critical question. And I really can’t answer it for you. This is why I’m asking you: do you need to know pitch accent? You have an idea of the costs of developing good pitch accent habits. Let’s now look at some differences between someone with a great pitch accent and someone with a foreign intonation, and you’ll be able to tell me if you find it worth studying.

The benefits of having good pitch accent

Good pitch accent makes you sound more fluent. This, in turn, means that the people you’re speaking with are less likely to adapt their language to what they think is your level and use easier words when communicating with you. If you sound like a native, people will more likely speak to you like a native. This means that if your goal is to better your Japanese, better pitch accent can lead to better occasions to learn more native-like expressions.

Good pitch accent is easier on your interlocutor. Japanese speakers have spent their entire lives hearing their language spoken in a distinct way. If you can adapt and match this natural flow of the language, the conversation will be much more engaging for the other person. A comfortable person is a person who talks more. More talk means more exposure. It’s also a great occasion to get to know the person better and make more friends.

What happens if I don’t have a good pitch accent

Bad pitch accent makes you sound less fluent than you are. Few things say I’m not confident in this language louder than a thick foreign accent. You might use complicated words and elaborate grammar, but many people unconsciously associate a good pronunciation with good mastery of the language, and vice-versa. This means that most people will speak to you more slowly, and try and dumb down the vocabulary they use. This is not bad if you’re using Japanese to get by while on vacation. This is more inconvenient if you’re trying to learn the native way of speaking.

Bad pitch accent doesn’t make it impossible to understand you, but… Unlike in tonal languages, in Japanese, some homophones may have different pitch accents, but rare are the occasions when what you mean cannot be inferred from context. The catch is that understanding you will demand some effort on the part of the person you’re speaking with to adapt. Doing this for an extended time can be uncomfortable and tiresome and make people want to talk less with you than if you had a more Japanese-like intonation.

Bad pitch accent makes you sound cute. There are not only bad sides to having a foreign accent. Speaking with a foreign intonation makes you sound cute to some speakers, who might be friendlier to you and overlook some of your mistakes. However, if you’re not a beginner learner, you might not want any of this 気遣い. Some people also see their foreign intonation as part of their identity and refuse to work on it. I see correct intonation as an integral part of the language I’m learning, but I can understand the argument they make. You do you.

In conclusion

Japanese pitch accent is not necessary to be understood, but it is not useless either, especially if you want to reach a higher level of Japanese. Ultimately, it all depends on what you want to do with Japanese. Don’t forget that Japanese, like every other language, is just a tool to pass information from one person to another. It’s yours to decide how sharp you need your tools to be for the job you have to do. You don’t need a scalpel to cut through butter.

This means you don’t have to stress (pun intended) over pitch accent if you only intend to use Japanese to communicate while travelling or for consuming Japanese content. People undertaking the efforts of learning pitch accent like to argue that it’s of the utmost importance that you study it too. It’s just a way of convincing themselves that what they are doing is not a waste of time. It’s not, but they shouldn’t have to pressure other people with different objectives into doing what they are doing. You should study Japanese pitch accent if you’re interested in mastering the language and its pronunciation—although pitch accent on its own is not enough. (more on that in a following blog post)

In any case, I think every Japanese learner should at least be aware that pitch accent is a thing. I also strongly encourage everyone to learn its fundamental workings. It also doesn’t hurt to double-check the correct pitch accent for words you use frequently, especially now that you know how numeric notation works. Whether you commit to learning pitch accent seriously or not depends on you and how you intend to use the language.

I hope this article helped you understand what pitch accent is, what the benefits of studying it are, and how to go about it so that you can decide whether to spend time and effort learning it.

As for myself? I’m studying pitch accent. I want to speak with people as naturally as possible and blend in without sticking out because of my foreign accent. I’m not the average learner, though, and although I think there are great things to be gained by studying pitch accent, I recognise that not everyone would need it. It is a non-negligible time investment, which might not be worth it if you don’t intend to speak the language much.